Here’s one prediction for 2022 that I can make with confidence but no joy: your social media feeds will continue to be polluted by misinformation, propaganda posing as fact, and bald-faced lies. No matter how much Facebook, Twitter and other platforms promise to crack down on bad actors, tweaking algorithms and banning the Marjorie Taylor Greenes of the world will be little more than fingers in a rapidly crumbling dike.

If we want things to change, we have to follow Gandhi’s advice and “be the change we want to see in the world.” That process begins by educating ourselves on the causes and scope of the problems we face, and then developing tools to fight back – to expose false narratives and replace them with more compelling stories based in truth, backed by science, grounded in reality.

To help you get started, we offer three books, three websites, and an additional reading list as curriculum for your very own “Fighting Misinformation 101” course. Registration is free and the cost of skipping this class is high, so dig in. There will be a test.

There is no shortage of excellent books about this age of Too Much Misinformation, so please consider the recommendations that follow only as a starting point:

The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark, by Carl Sagan & Ann Druyan (Random House © 1995)

The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark, by Carl Sagan & Ann Druyan (Random House © 1995)

To begin to understand why human beings are so vulnerable to myths, conspiracy theories, and outright lies, start here. Published in 1995 – well before smart phones, social media and Fox News even existed – The Demon Haunted World is a passionate defense of science in general and the scientific method in particular. Covering a wide swath of history from 17th century witch trials all the way to (then) contemporary claims of alien abductions, Sagan and Druyan make the case that accepting fact-free explanations and ignoring contradictory scientific evidence is not new behavior. Smash cut to America 2022, a nation awash in Big Liars, global warming deniers, and anti-vaxxers, and you’ll find that Sagan & Druyan’s book feels even more relevant 27 years after its original publication.

True Enough: Learning to Live in a Post-Fact Society, by Farhad Manjoo (John Wiley & Sons © 2008)

True Enough: Learning to Live in a Post-Fact Society, by Farhad Manjoo (John Wiley & Sons © 2008)

Stephen Colbert mined the concept of “truthiness” – the idea that if something feels true, that’s good enough – for satire, but Farhad Manjoo is more interested in how it has dangerously impacted politics, business, and culture in general. Manjoo builds on the arguments begun by Sagan and Druyan in The Demon-Haunted World and brings them into the 2000s by focusing on 9/11 conspiracy theories and the 2004 “swift-boating” of John Kerry. He maintains that human proclivities towards selective perception and confirmation bias, compounded by social media feeding us only the facts we want to see, have effectively divided Americans into more than just separate ideological camps. We are actually living in separate realities.

Post-Truth, by Lee McIntyre (MIT Press © 2018)

Post-Truth, by Lee McIntyre (MIT Press © 2018)

Lee McIntyre, a Research Fellow at the Center for Philosophy and History of Science at Boston University, covers similar territory to True Enough, but he adds an interesting philosophical analysis that deepens our understanding of how we got here. In Chapter 6, “Did Postmodernism Lead to Post-Truth?”, McIntyre defines postmodernism this way: “The first thesis of postmodernism [is that] there is no objective truth. Any profession of truth is nothing more than a reflection of the political ideology of the person who is making it.” With this definition in hand, McIntyre draws a straight line from postmodern philosophers such as Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault to modern day pathological liars such as Donald Trump and Kellyanne Conway and ultimately concludes “postmodernism is the godfather of post-truth.”

And if you want to check out additional titles in this growing field of literature, take a look at “Ten Good Books About Bad Information.”

We also recommend visiting the following websites to find tools for battling misinformation and, happily, some comic relief as well.

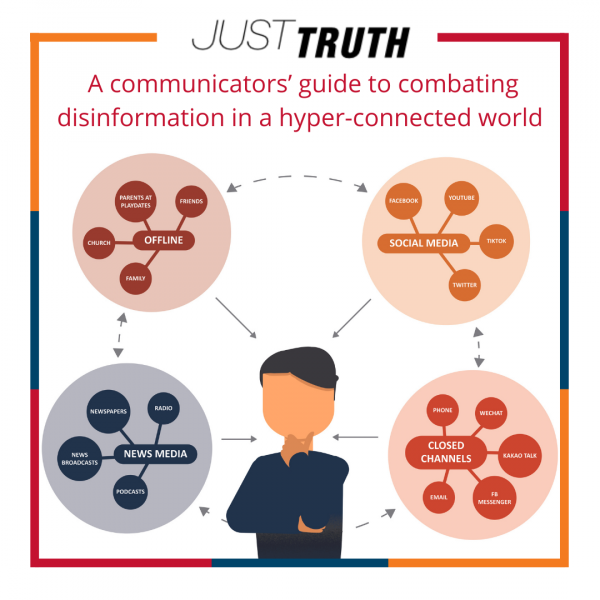

Just Truth: A communicator’s guide to combating disinformation in a hyper-connected world.

Just Truth: A communicator’s guide to combating disinformation in a hyper-connected world.

Whether to preserve corporate interests, hoard political power, or maintain white supremacist and patriarchal systems, false narratives have been disseminated for decades (or even longer) in the U.S., and it’s only getting worse as we enter 2022. Convinced that fighting disinformation is a teachable skill that public interest organizations need to develop, Spitfire Strategies recently launched “Just Truth.” Through this free online guide, Spitfire is collecting and sharing existing research on disinformation techniques and campaigns to help progressive nonprofits battle them more effectively in their communication efforts.

While fake news is a serious problem, teaching people how to recognize it doesn’t have to quite so serious – or so says Jon Roozenbeek, co-creator of the online game “Bad News.” The conceit of this game is that it teaches players how to be a purveyor of fake news. As you play, you earn badges for developing six sinister skills: impersonating other tweeters (especially anyone more famous or credible than you), touting conspiracy theories, antagonizing highly polarized groups, discrediting sources (particularly anyone who dares to criticizes you), trolling, and using emotional content. The real purpose of the game, however, is not to educate a new legion of online scammers, but instead to, as Roozenbeek puts it, “create what you might call a general ‘vaccine’ against fake news, rather than trying to counter each specific conspiracy or falsehood.” Does this particular “vaccine” work? Play the game and see for yourself!

While Jon Roozenbeek is battling the onslaught of fake news with a game, Peter McIndoe is going one step further. The 23-year-old from Memphis is trying to beat the fakers at their own game by spreading the most outrageous lie he can think of: birds aren’t real. They are drones built by the government to spy on us and carry out other nefarious tasks. The avian awareness campaign which McIndoe began as a lark (sorry, couldn’t resist) in 2017, has developed a life of its own, spawning chapters across the country, spreading its message on billboards and t-shirts, and generating tons of free media coverage. “It’s a safe space for people to come together and process the conspiracy takeover of America,” McIndoe told The New York Times last December. “It’s a way to laugh at the madness rather than be overcome by it.”