Somber music plays behind hard-to-watch pictures of starving children. The voiceover begins: “The need is painfully evident in their eyes, in their tiny bodies that weigh no more than young babies. In their desperate struggle to find any means to survive, and in their loss of hope that help will ever arrive in time. Sixteen million people are on the brink of starvation here in East Africa, and hunger takes its toll in many brutal ways.”

This is a verbatim excerpt from a PSA intended to raise money to end hunger, and if the script sounds familiar, that’s because it’s a recipe that has been used for decades. Start with a problem; add some music, sad pictures, and a sad tale; ask for money. The formula can work, but take a step back and you’ll see a bigger problem. It’s called “deficit framing.”

In stories told with deficit framing, the people we meet are already in a distressed or perilous state. They are starving, homeless, addicted to drugs, or a victim of abuse. Stories told this way may evoke emotion, but that tends to be pity instead of empathy. The people who are experiencing hardship appear as objects at the mercy of events and without agency to change things. This also strengthens a savior-style narrative that positions the organization as the only thing (along with your dollars, of course) that can fix these broken people.

Fortunately, this ethical trap in storytelling can be avoided through a practice called “asset-framing.” Trabian Shorters, a leading expert and advocate for asset-framing, calls it “a narrative model that defines people by their assets and aspirations before noting the challenges and deficits.” This means your story introduces the protagonist (i.e., who the story is about) as a person with accomplishments, hopes and values before we get to the challenges that ultimately led them to your organization.

Fortunately, this ethical trap in storytelling can be avoided through a practice called “asset-framing.” Trabian Shorters, a leading expert and advocate for asset-framing, calls it “a narrative model that defines people by their assets and aspirations before noting the challenges and deficits.” This means your story introduces the protagonist (i.e., who the story is about) as a person with accomplishments, hopes and values before we get to the challenges that ultimately led them to your organization.

Consider the following transcript from a video posted on the website of Pathfinders, a nonprofit that offers services to people who experience homelessness. The guest speaker, Yolanda Seely, talks about her journey into and out of homelessness, but before she gets to any of that, she will tell you a few things about herself:

“My name is Yolanda Sealy. I was born and raised in Rantoul, Illinois. I’ve always been a hard worker, and in high school I was a triathlete. I played basketball, volleyball and I ran track, and I was an honor student. My talents earned me a Division One scholarship. I played basketball at the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana. When I graduated from the University of Illinois, I moved to Houston, TX and shortly after I joined the United States Army. I served eight years in the army active duty and two years Army Reserve. I’m a mother of two beautiful girls: Ariana, my daughter who’s 14 and Ariel, who’s three years old. And those are the joys of my life.”

Asset-framing is not only a more ethical way to tell stories – it’s fundamentally sound story structure.

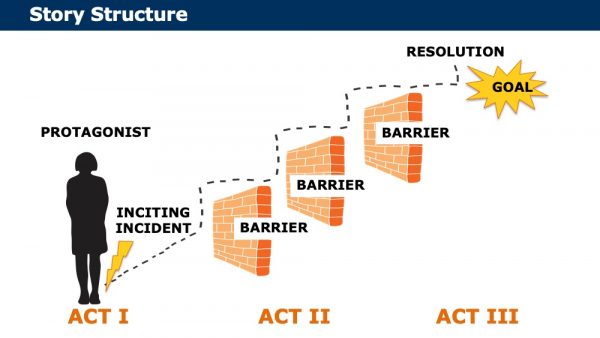

Act 1: We introduce the audience to a protagonist – someone they can care about and root for through the rest of the story. In the Pathfinders example, that’s Yolanda: a loving mom, a college graduate, and a veteran. Then comes the inciting incident, the event that kicks the story into motion and gives the protagonist a goal: Yolanda loses her job. Now she must find a way to keep food on the table for her children.

Act 1: We introduce the audience to a protagonist – someone they can care about and root for through the rest of the story. In the Pathfinders example, that’s Yolanda: a loving mom, a college graduate, and a veteran. Then comes the inciting incident, the event that kicks the story into motion and gives the protagonist a goal: Yolanda loses her job. Now she must find a way to keep food on the table for her children.

Act 2:Our protagonist encounters barriers: hardships, struggles and brick walls. Yolanda loses her apartment, and without someplace to live, it is nearly impossible to find a job. Yolanda is not one to give up, however, and working with Pathfinders she finds ways to surmount these barriers.

Act 3: This is where the story resolves and the meaning becomes clear. Yolanda has a home again and has recovered the self-sufficiency she valued about herself. She’s changed and she’s learned a lot, and we have some new insights into exactly how Pathfinders works with the people it serves.

If you tell stories with deficit-framing, you are starting with the barriers. Go back to that PSA about starving children in East Africa at the beginning of this article. It skips Act I and goes straight to the barriers of Act II! To a certain extent, this mistake is understandable. When organizations tell stories about people they have served, they start from the moment they met them. But that isn’t the beginning of their story.

Every person has a whole story before they meet us. They have aspirations and accomplishments, they have values, things and people they love. That’s how we should get to know them. Before the inciting incident. Before the barriers. Because you want the audience to see themselves in this person. Because you want them to feel compelled to act. Because you are striving to create empathy, not pity.

And because it’s also better storytelling.